Gut bacteria: the smart helper in the fight against cancer

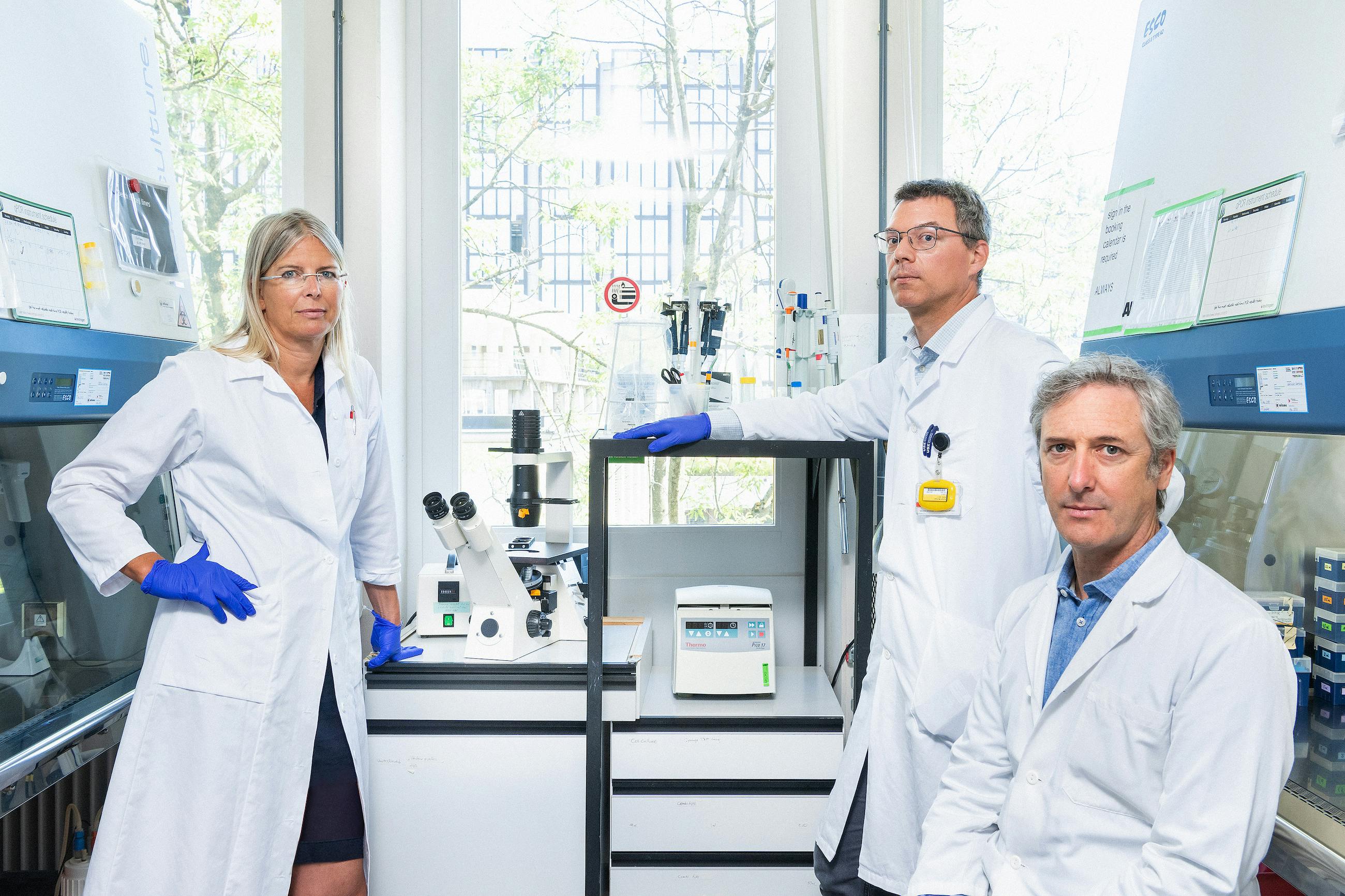

The composition of the intestinal flora can have a decisive influence on whether immunotherapy used to treat cancer will be successful or not. Researchers at the University of Zurich and the University Hospital Zurich are pooling their strengths as part of the Cancer-MicroBiome project: the crack team of gastroenterologists, dermatologists, and oncologists are aiming to figure out the mechanisms that boost the immune system and thus put cancer in its place.

Contact

Prof. Dr. med. Michael Scharl

Chief of Service in the Department of Gastroenterology and Hepatology

at University Hospital Zurich and professor of translational microbiome research at the University of Zurich

+41 44 255 34 19

michael.scharl@usz.ch

UMZH institutions

University of Zurich

University Hospital Zurich

Team

Recovered patients donate their stool

At University Hospital Zurich, Marianne Schütz* is meeting gastroenterologist Prof. Michael Scharl for a consultation. She is one of five former cancer patients selected to play an important role in the Cancer- MicroBiome project being run by the Comprehensive Cancer Center Zurich. When Marianne was diagnosed with skin cancer five years ago, she was given immunotherapy. She is now tumor-free. In her case, the immunotherapy – known as immune checkpoint blockade – worked. Unlike chemotherapy or radiotherapy, this treatment does not kill the tumor, but pits the immune system against it by releasing a kind of «brake» holding back the immune cells so that they can tackle the tumor cells more aggressively.

Michael Scharl is a professor involved in translational microbiome research at the University of Zurich and in gastroenterology at University Hospital Zurich. He believes that, in addition to the immunotherapy, the microorganisms in Marianne Schütz’s intestine helped conquer her cancer. That is why she has now become a donor, because the composition of her intestinal flora – her microbiome – could help other cancer patients who have either not responded or not responded well enough to immune checkpoint blockade treatment. The process of transplanting bacteria from another person into a patient’s own intestine is also known among specialists as a fecal microbiota transplant (FMT). Small pilot studies have shown that stool transplants can support the treatment of patients with advanced melanoma. The Cancer-MicroBiome project team is now hoping to get to the bottom of this.

Michael Scharl describes the aim of the project as follows: «We want to figure out the key bacteria and molecular mechanisms between the microbiome and the immune system so that we can increase the effectiveness of immunotherapy in fighting cancer.» To achieve this, plans are being made at University Hospital Zurich to perform stool transplants on patients with skin, lung and other types of cancer who – unlike Marianne Schütz – have not responded to immunotherapy. The first stage, scheduled to begin in July 2022, involves transferring stool samples from people who have recovered from cancer to current cancer patients.

They want to revolutionize cancer treatment – with the help of gut bacteria: Anne Müller, Michael Scharl, Mitchell Levesque (from left to right)

The hunt for medical clues

In parallel with the transplants, various researchers are looking into the connection between bacteria and the immune system. The basic hypothesis is that immune cells in the intestinal mucosa recognize signaling molecules produced by bacteria, which affect the immune response. «We already have our eye on various immunomodulators of this kind,» says Prof. Anne Müller, a professor of experimental medicine at the Institute of Molecular Cancer Research at the University of Zurich. She has been conducting research using mouse models and is working closely with Michael Scharl. The mice receive the same stool transplants as the patients at University Hospital Zurich, except that they are given to the animals orally. A mouse’s stomach is less acidic than a human’s, so the microbes can get into the intestine undamaged and unleash their effect.

Anne Müller hopes that the stool transplants will be seen to have a positive impact in animal models too. The idea here is to use this method to treat mice with cancer in parallel with the immunotherapy. The hope is not only that the stool transplants will make the tumors go away completely, but also that the researchers can gain a better understanding of the mechanism behind the effect of these transplants. «This will mean we can make a prognosis thanks to our work,» says Müller. «If we see that a particular donor’s stool is working in a mouse, it might also work in a human.»

Prof. Mitchell Levesque, a professor of experimental immunodermatology at the University of Zurich, is also involved in the project. He is looking for medical clues or signs, known as biomarkers, that could indicate why certain patient groups do not respond to immunotherapy. This is an area where researchers are still in the dark. They still do not know, for example, whether this is down to metabolites or the bacteria themselves boosting the immune system, or whether it is due to a lack of microbes.

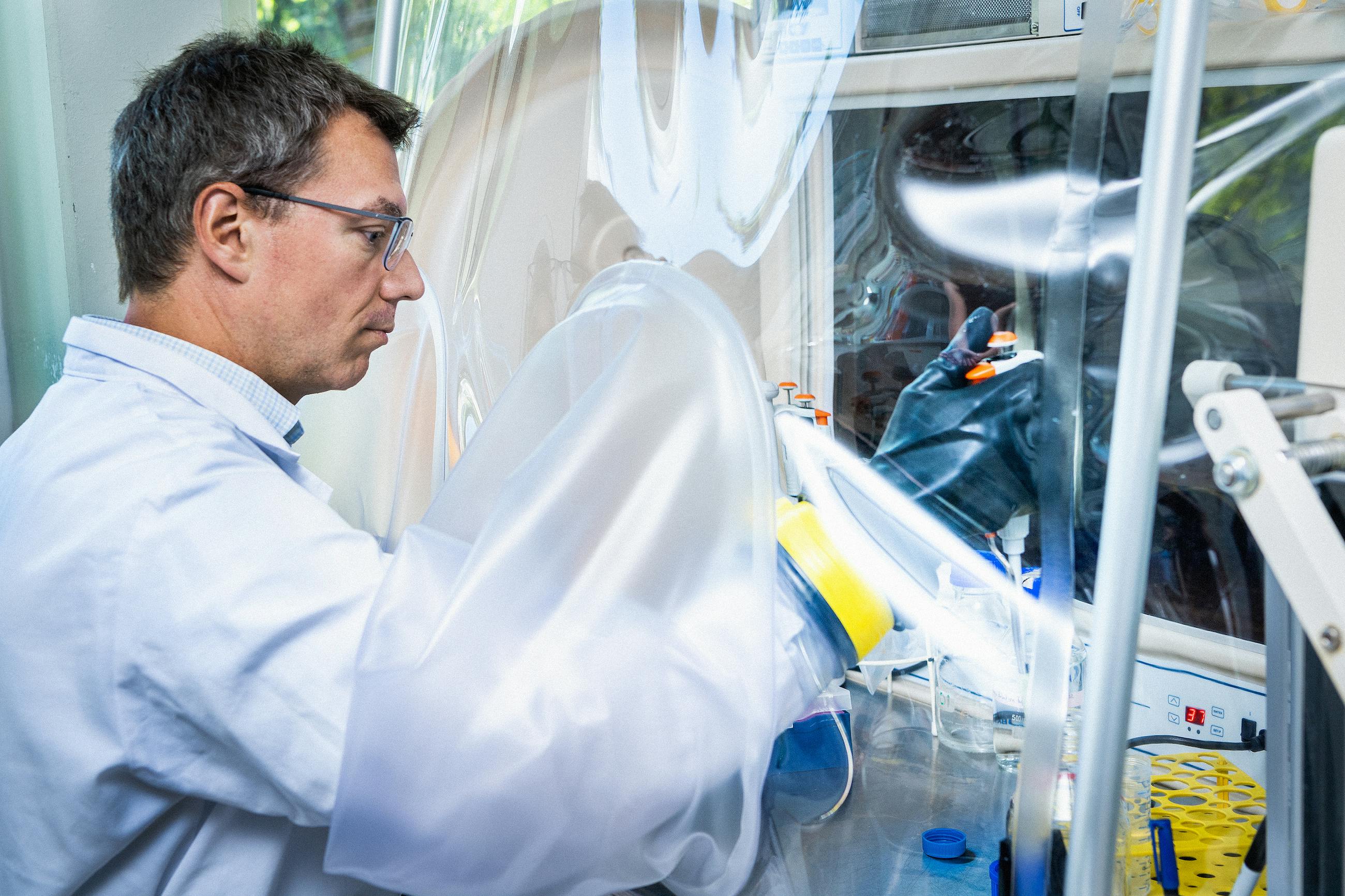

Wants to increase the effectiveness of immunotherapy in fighting cancer: Michael Scharl in the laboratory at the Comprehensive Cancer Center Zurich.

Checkpoints block tumor cells

The immune system’s ability to distinguish between normal cells and harmful ones primarily depends on regulators known as checkpoints, which are attached to the surface of the powerful T-cells that form part of the immune defense. A healthy cell activates certain checkpoints on the surface of the T-cell and is therefore identified as a natural part of the body. Abnormal cells, even though they are recognized as such by the T-cells, activate the same checkpoints and thus deceive the immune system. This is where immunotherapy comes in. The checkpoints on tumor cells are blocked with the help of synthetic antibodies known as checkpoint inhibitors. No longer outwitted, the immune cells promptly turn on the malignant tissue in force. «Immune checkpoint blockade therapy has revolutionized cancer treatment,» Mitchell Levesque remarks emphatically. Nevertheless, the cancer continues to progress in a large proportion of patients because they are not responding to immunotherapy.

Transferring bacteria during colonoscopy

Scharl’s team of scientists is now taking a pragmatic approach. They are transplanting stool from five people who have had cancer but responded exceptionally well to immunotherapy and have now been cancer-free for several years into 25 cancer patients who have not had a successful experience with immunotherapy. Marianne Schütz is one of these «super donors.» After completing a safety check, which also covers known pathogens, her particular mix of bacteria is transferred to the large intestine of a test subject who has skin cancer. This is done by means of a colonoscopy procedure.

The microbiome: an innovative approach for precision oncology

It is not yet possible to make a clear distinction between good and bad microbes among the thousand or more different species of bacteria that are normally found in the human intestine. With their microbiome study, the researchers want to find out which bacterial species or microbiological products are conducive to an effective immune system. Analyses of the microbiome in the gut produce huge quantities of data – around 10 terabytes per patient. In addition to this, Scharl and his team are also collecting information from, for example, blood cells, serum, intestinal tissue, cancer tissue, and stool. All of this is being examined at molecular level. «We are looking at what kind of metabolites the bacteria produce and analyzing their effect on immune cells,» says Scharl.

These efforts are all in aid of improving future treatment for patients: in the long term, the interdisciplinary team under Michael Scharl, Anne Müller, and Michael Levesque hopes to be able to provide customized microbiome transplants. An even better outcome would be if the right microbe mix could eventually be prescribed in tablet form.

*Name changed by the editors.

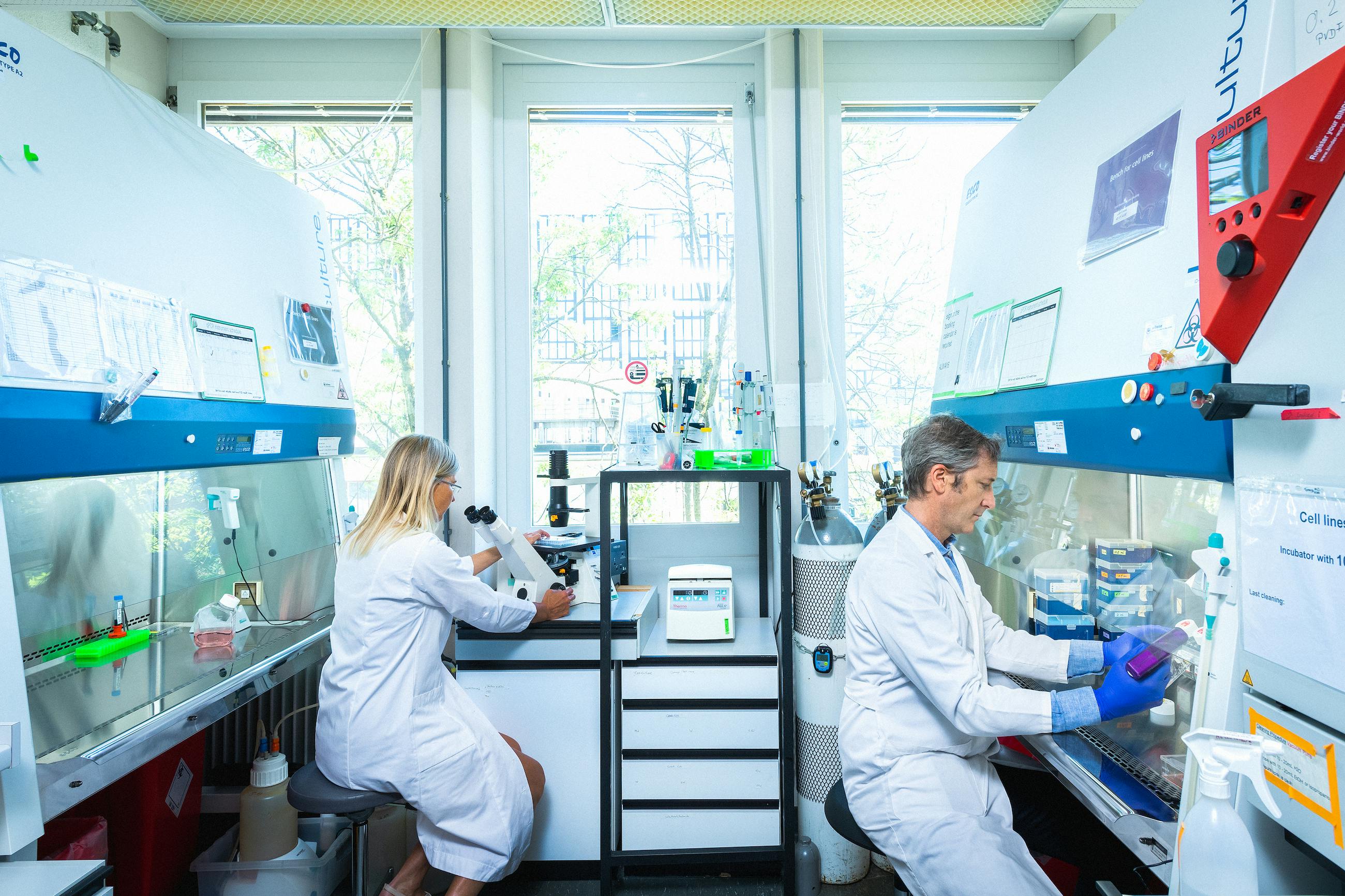

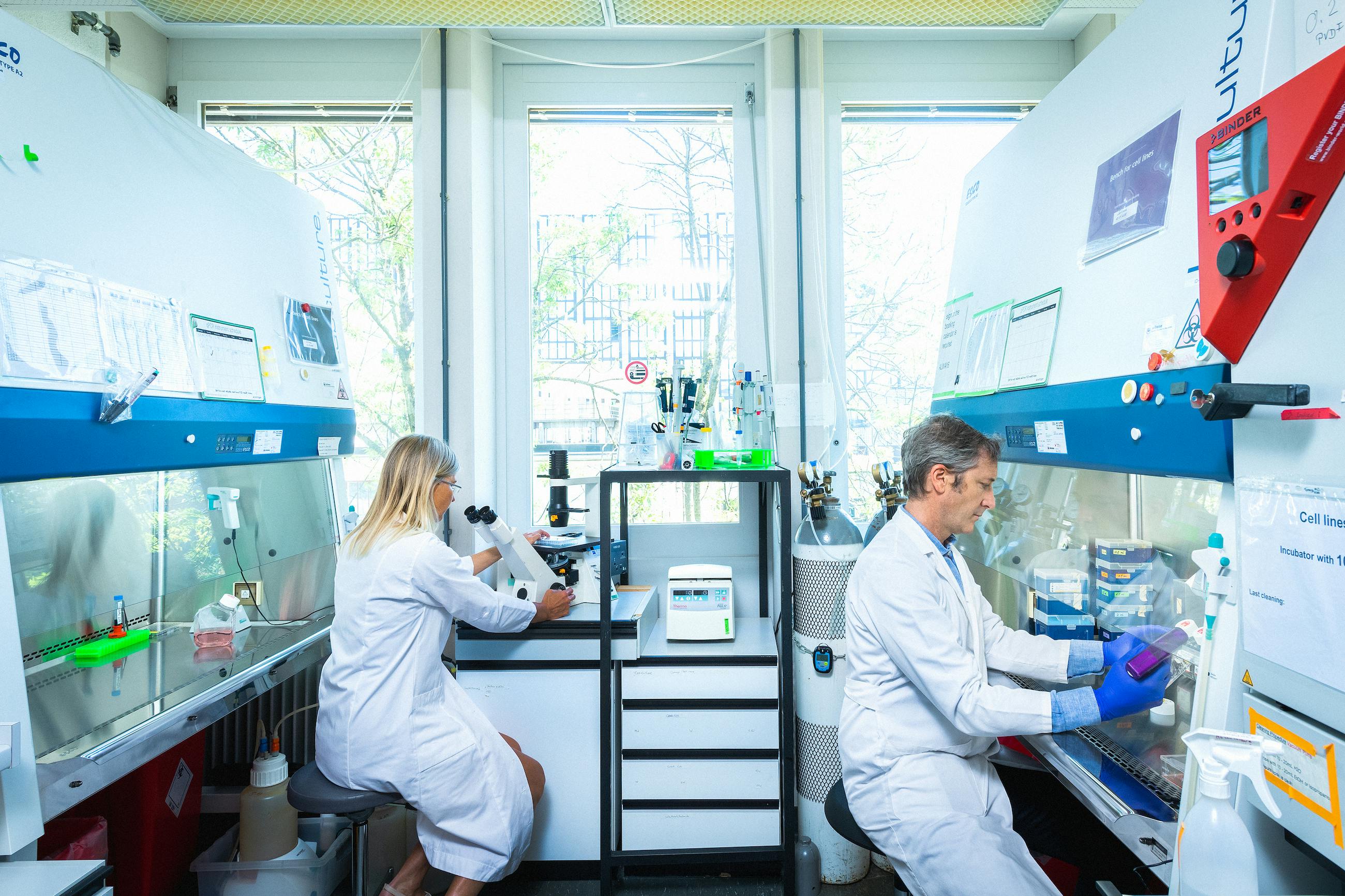

Stool from cancer patients is examined at molecular level.

Listen

Anne Müller (Audio file in German)

«Gut bacteria influence the effectiveness of immunotherapy»

Prof. Anne Müller is a professor of experimental medicine at the Institute of Molecular Cancer Research at the University of Zurich.

Michael Scharl (Audio file in German)

«By transplanting stool, we can make immunotherapy more effective against cancer»

Prof. Michael Scharl is Chief of Service in the Department of Gastroenterology and Hepatology at University Hospital Zurich and a professor of translational microbiome research at the University of Zurich.

Mitchell Levesque

«Our study is revolutionary. It changes our perspective on how we treat cancer»

Prof. Mitchell Levesque is a research group leader in experimental immunodermatology in the Department of Dermatology at University Hospital Zurich and a professor in the Faculty of Medicine at the University of Zurich.

Patient (Anonymous, audio file in German)

«For me it was clear that I would participate in the study»

The patient is a recipient of a stool transplant.

Service

Would you like a second opinion?

Our joint center of excellence, the Comprehensive Cancer Center Zürich offers cancer patients a specialist expert opinion to help them to make an informed decision.

Dermatology online: University Hospital Zurich’s online skin check tool (in German)

Microbiome: Clinic at University Hospital Zurich

Glossary

Microbiome:

The microbiome refers to all of the microorganisms that live in the gut.

Checkpoint inhibitors:

Checkpoint inhibitors are a type of immunotherapy. These are designed to release the brakes on the body’s immune system. This strengthens its existing but inactive immune response and fights the cancer.

Fecal microbiota transplant:

Transplanting the gut bacteria of one person into the intestines of another person using colonoscopy.

T-cells:

T-cells are a kind of white blood cell, and are an important part of the body’s immune defenses. They recognize cells that are infected with a virus and kill them.

Gastroenterology:

Gastroenterology/hepatology covers the diagnosis and treatment of stomach, intestinal, pancreatic and liver diseases.

Translational research:

The results of translational research are «translated», i.e. made suitable, for use in everyday clinical practice.

Melanoma:

Melanoma is a kind of malignant tumor that results from the degeneration of melanin-generating cells in the skin. It is not the most common type of skin cancer, but is the most malignant. Melanoma can metastasize and is responsible for more than 90 percent of all deaths from skin cancer.

Who is co-financing this project? (in CHF millions)

CCCZ

The project funding lasts from

2022 to 2025

Credits

Text and audio: Rebekka Haefeli, Marita Fuchs

Pictures: Frank Brüderli

University of Zurich: Anne Müller, Michael Scharl, Mitchell Levesque

University Hospital Zurich: Michael Scharl, Mitchell Levesque, Christian Britschgi