Research brings hope for

children with aggressive brain tumors

Brain tumors may be rare in children, but that makes them all the more dangerous. Despite medical advances, there is still no prospect of a cure for the more aggressive forms. In Zurich, teams involved in basic research are joining forces with clinicians to improve prognoses for children with these kinds of tumor. Their analyses of cell material are already pointing the way toward potential new therapies.

Contact

Prof. Dr. Javad Nazarian

Professor at the Faculty of Medicine of the University of ZurichDirector of the DIPG/DMG research center at University Children’s Hospital Zurich

+41 44 510 74 57

E-Mail

UMZH institutions

University of Zurich

University Hospital Zurich

ETH Zurich

University Children's Hospital Zurich

Team

It is a shattering diagnosis: The parents of six-year-old Emma* discover that their daughter is suffering from a rare, aggressive brain tumor. Most people diagnosed with this type of tumor, known as diffuse intrinsic pontine glioma (DIPG), only survive for nine to twelve months post-diagnosis. Only 10 percent of patients survive for two years after this point. The cause of gliomata, i.e. tumors of the brain and spinal cord, is largely unknown in the case of children and young people. Studies have examined connections between environmental and infectious influences, but only exposure to ionizing radiation has emerged as a potential risk factor. It is now known thanks to molecular studies of tumor tissue that pediatric gliomata are not the same as those found in adults. The experience acquired to date in the field of adult tumor medicine cannot really be applied to children.

In Emma's case, the images from an MRI scan present a clear picture: The glioma is located on her brain stem and so closely interwoven with the surrounding brain tissue that surgery is impossible. Any surgical intervention would damage too much of the brain’s healthy tissue.

Unique study to increase life expectancy

Previously, the only available therapy option for brain tumors such as DIPG and diffuse midline glioma (DMG) was radiotherapy. This increased life expectancy by just a few months. Physicians treating patients found their hands were tied. Today, there is hope for Emma – maybe not of a cure, but certainly of increased life expectancy. The young patient has the opportunity to participate in a study being conducted by the DIPG/DMG Center. Professor Sabine Müller is the Clinical Director of the Zurich-based research center, which is receiving financial support from Academic Medicine Zurich (UMZH). “In recent years, our understanding of the biology of these tumors has significantly improved, and it is now clear that DMGs, including DIPGs, are a heterogeneous group of tumors that require a personalized approach to therapy,” says Müller.

Javad Nazarian is a professor at the Faculty of Medicine at the University of Zurich and heads up the research laboratory at the DIPG/DMG Center. “Research to date has neglected rare cancer types in children,” explains the academic. The center was founded with the aim of developing new therapies for children with rare gliomata (DIPG and DMG). The research group strives to discover new biomarkers that will help us better understand the response to therapies or why they fail.

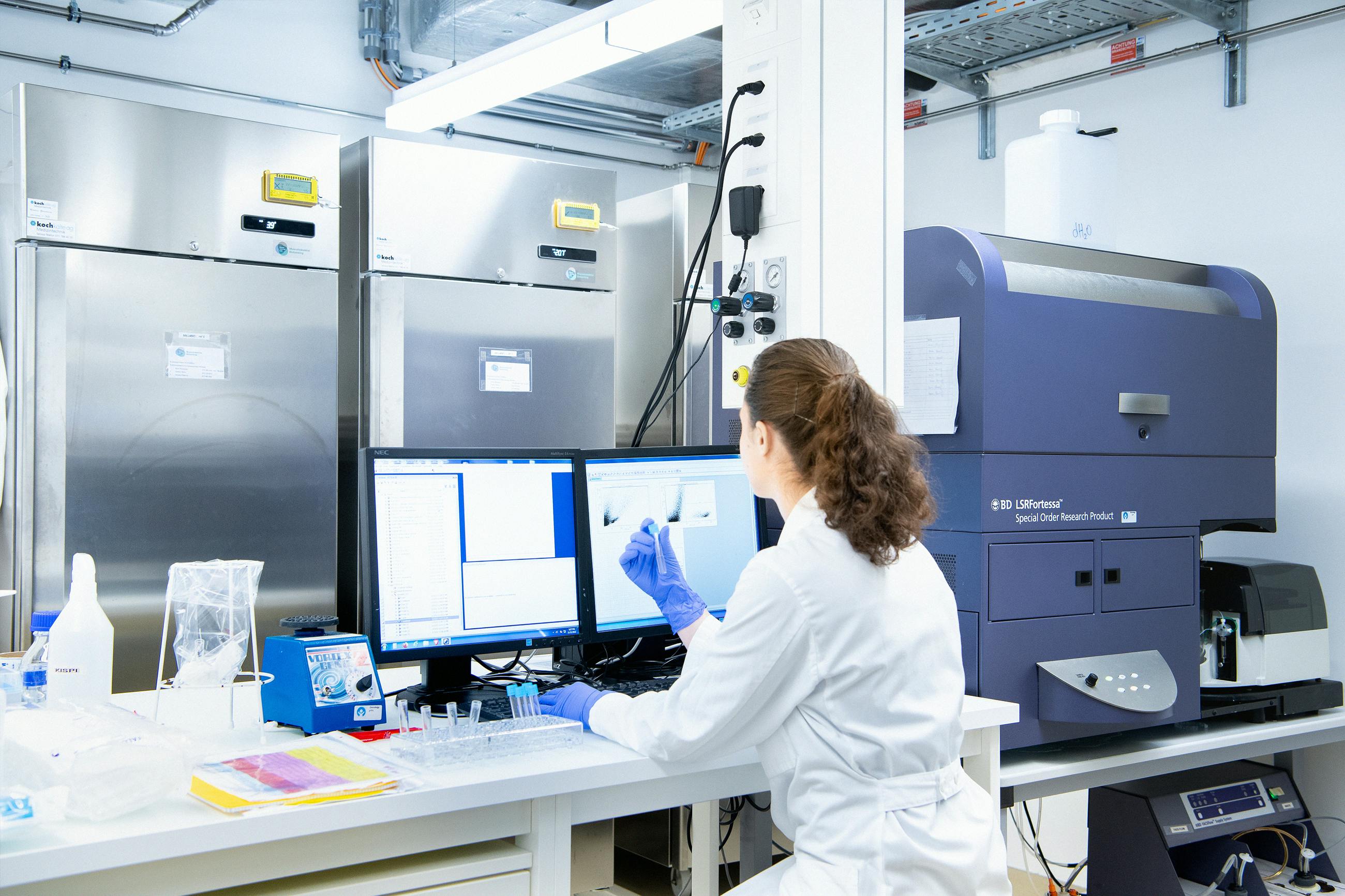

The academics involved evaluate and research new therapy options by testing active ingredients on patients’ own tumor cells. They study cell models that replicate the characteristics of human cancers. And they work on discovering novel drugs and combinations of drugs that could be directly transferred to clinical practice and therefore help children affected.

Talking openly with children

Just like the young patients taking part in the study, Emma and her family are also being supported by the oncology team at University Children's Hospital Zurich. One of these physicians is the oncologist Ana Guerreiro Stücklin. “Tumors that used to be broadly classified as pontine gliomata will actually differ from person to person and vary significantly in terms of their biology and clinical course,” points out Guerreiro Stücklin. She explains to Emma’s parents that the molecular and genetic analysis of the tumor tissue, blood, and spinal fluid taken from their daughter may provide important clues about the type of tumor. As each cancer is unique, any treatment with drugs should also be specifically tailored to Emma.

The oncologist has a wealth of experience in talking to parents, who generally feel overwhelmed and devastated following a brain tumor diagnosis. She advises family members to talk openly with their child. “Children can tell immediately when adults are hiding something from them,” says Guerreiro Stücklin. It is better to explain what has happened, in a way the child can understand, and talk them through the individual treatment phases.

Individual data thanks to biopsy

The first step toward diagnosis is the biopsy. Right up to the late 1990s, this was not recommended for children with DIPG as the risk of injury was just to great. Only imaging techniques were used previously. There has been a fundamental shift since, with tissue removal now possible thanks to advances in neurosurgery over recent decades. “We have developed a systematic procedure for safe, robot-supported biopsies of the brain stem,” explains Müller. The tumor material removed is analyzed at the molecular level in the laboratory. The data acquired this way provides valuable knowledge in terms of tumor prognosis and individual treatment strategies and does so within a clinically relevant time frame.

In the laboratory, researchers analyze tumor tissue at the molecular level.

Close collaboration between research and clinical practice

This is true for Emma too: The team at the DIPG/DMG Center examines the young patient’s tissue to better understand the biology of her tumor. In the laboratory, the academics reproduce the cells removed – an often difficult and laborious task. They then test the various active ingredients and can draw important conclusions: “We are well on the way to finding effective therapies for some of the most complicated types of childhood cancers,” says Nazarian. For example: “With DIPGs, we have seen a slight improvement in overall survival rates for our patients in the past two years.” In addition, immunotherapies and other studies, including ones targeting tumor metabolism, have shown some initial clinical success. In the case of tumor metabolism, all the various biochemical processes that occur within cells are examined. “Sadly, we still do not know how to cure the children affected. In order to do this, we need to combine sound strategies that target the relevant biology,” says Nazarian.

Impressed by children’s strength

Once drugs that may be able to help with a given tumor are identified, the blood-brain barrier presents another obstacle to overcome. This barrier regulates the exchange of substances between the blood circulatory system and the central nervous system. Its main function is to protect the brain against infections and unwanted molecules. But the barrier also hinders the transfer of effective therapies to the tumor. “One of the new technologies is focused ultrasound (FUS), which uses microbubbles to open up the barrier,” says Nazarian. A number of clinical studies are currently investigating the safety of this technique. “We believe that FUS will revolutionize the treatment of brain tumors in children.”

While researchers in the laboratory are looking for the best drug therapy, Emma is undergoing radiotherapy sessions at the Paul Scherrer Institute, which has equipment that can target the tumor with real precision. Emma is accompanied by an employee from the anesthesia team at University Children's Hospital Zurich. He gives her a sense of security and keeps her calm. Emma is brave and knows she must keep still while radiotherapy is performed. Her family too have now found some hope.

Once the right mix of drugs has been found for Emma, everyone hopes that she will respond to therapy. Ana Guerreiro Stücklin is supporting the little girl on this journey. The oncologist finds the motivation for her work on the clinical side of things. “I realize how important research is, particularly when parents ask whether there is nothing more we can do for their child.” And she is continuously impressed by the strength that children show and how they manage – in spite of everything – to retain their will to live.

*Name changed

The new University Children’s Hospital Zurich-Lengg will open its doors in the fall of 2024. The construction project also includes a new building for research and teaching. Research is already under way, with various research teams – under Prof. Jean-Pierre Bourquin, the Senior Physician for Oncology at University Children's Hospital Zurich – working on new therapeutic approaches aimed at further improving chances of recovery for children with rare cancers. The teams consist of researchers from the University of Zurich, ETH Zurich, and the University Children's Hospital Zurich. The DIPG/DMG Center Zurich is part of Campus Lengg and is mainly concerned with developing and implementing improved therapies for children with a DIPG/DMG diagnosis. The academics at the research center assess and research new therapy options, which may then be transferred to clinical practice.

Studies at the center are conducted in collaboration with the Pacific Pediatric Neuro-Oncology Consortium (PNOC) Sabine Müller is the Director. PNOC is an international consortium with centers in the US, Europe, Asia, and Australia. Its objective is to offer new therapies to children and young adults with brain tumors.

Listen

Javad Nazarian

«In Zurich, we’ve treated 300 children so far from around the world with rare brain tumors»

Professor Javad Nazarian is the Director of the DIPG/DMG research center at University Children’s Hospital Zurich and a professor at the Faculty of Medicine of the University of Zurich. He is also Associate Professor for Pediatrics at the George Washington University in Washington D.C., USA.

Sabine Müller (Audio file in German)

«I’m more hopeful than ever – we’re close to developing therapies for affected children»

Professor Sabine Müller is the chief of service for oncology at University Children’s Hospital Zurich and heads the clinical program for the DIPG/DMG center in Zurich. She is an adjunct professor at the Faculty of Medicine of the University of Zurich and a professor at the University of California San Francisco (UCSF).

Ana Guerreiro Stücklin (Audio file in German)

«Our project supports more targeted therapies for affected children»

Professor Ana Guerreiro Stücklin is a pediatric neuro-oncologist at University Children’s Hospital Zurich and a professor at the Faculty of Medicine of the University of Zurich.

Sarah Brüningk (Audio file in German)

«We learn from data and draw conclusions for potential new treatment methods»

Dr. Sarah Brüningk is a postdoctoral researcher at the Institute for Machine Learning and Computational Biology, which is part of ETH Zurich.

Services

Support for parents: When a child is seriously ill, this can be very hard for the whole family. The University Children's Hospital Zurich offers parents and relatives various types of support, such as welfare advice, visiting and child-minding services, or psychological help.

Second opinion: Families of children affected may approach the DIPG/DMG Center. They are entitled to an assessment and second opinion from the research team.

Glossary

Biopsy:

During a biopsy, health care professionals take a sample from an area of tissue showing noticeable changes.

Blood-brain barrier:

The blood-brain barrier is an organic barrier between the blood circulatory system and the central nervous system.

Diffuse intrinsic pontine glioma (DIPG):

A malignant tumor that grows in a specific area of the brain stem (the medical term for this area is the pons). It is a rare form of cancer that mostly occurs in children.

Diffuse midline glioma (DMG):

These malignant tumors occur in the midline structures of the brain such as the thalamus, brain stem, and spinal cord.

Magnetic resonance imaging:

Magnetic resonance imaging, or MRI for short, is a kind of imaging process. It creates layers of images from inside the body, which can be used to study the structure and function of organs and tissue.

Who is co-financing this project? (in CHF millions)

Credits

Text and audio: Marita Fuchs, Rebekka Haefeli

Pictures: Frank Brüderli

University of Zurich: Ana Guerreiro Stücklin

ETH Zurich: Sarah Brüningk

University Children's Hospital Zurich: Ana Guerreiro Stücklin, Sabine Müller, Javad Nazarian